Introducing Crypto Circular Economies

An experimental real-world use case for cryptocurrencies.

Most of the talk around crypto going 'mainstream' refers to investing. However, looking at crypto exclusively through the lens of speculation strays from the founding ideology behind some of the oldest projects in the space. Bitcoin, by far the largest cryptocurrency by market cap ($330 billion at the time of writing), and one of the oldest, was never meant to serve as an investment vehicle. The original Bitcoin white paper by Satoshi Nakamoto is called "A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System". (Emphasis added.) To contextualize the problem that they were designing Bitcoin to solve, Nakamoto refers specifically to commerce: "Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments." Bitcoin's raison d'être is therefore to enable electronic payments while circumventing financial institutions and the cost overhead they add to transactions.

To focus exclusively on cryptocurrency as an investment is therefore missing the point. The dramatic rise in crypto prices and the vast fortunes some have amassed (and others have lost) as a result makes for spectacular headlines. However, this angle both neglects and negates the disruptive potential of cryptocurrency and the powerful ideas behind it. It also fuels criticism. Crypto detractors (particularly central banks and financial regulators) have repeatedly cited the failure of crypto to function as a means of payment as one of its greatest shortcomings:

Satoshi Nakamoto’s dream of creating trustworthy money remains just that – a dream.

... [a] large majority of crypto holders rely on intermediaries, contrary to the avowed philosophy of decentralised finance. In El Salvador, for instance, which is the first country to adopt bitcoin as legal tender, payments are carried out via a conventional centrally managed wallet.

So crypto-assets are speculative assets that can cause major damage to society. At present they derive their value mainly from greed, they rely on the greed of others and the hope that the scheme continues unhindered. Until this house of cards collapses, leaving people buried under their losses.

For a few cryptos more: the Wild West of crypto finance (Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB)

There is some irony in an establishment figure invoking the image of a "house of cards" to denigrate crypto while speaking at an event in New York City. After all, this was ground zero in the 2008 financial crisis, which revealed the entire system of traditional finance to be just what crypto is often accused of: a house of cards built on a foundation of greed.

Referring to crypto as a "scheme" (as others in addition to the ECB have done), seems gratuitous and unnecessarily polarizing. Schemes typically require a mastermind - someone who pulls the strings and ultimately reaps the rewards. There is usually some level of deception involved as well. While some crypto projects could fairly be described as a scheme along these lines, this is not true as a general statement. Not to mention that traditional finance is replete with examples of schemes as well.

One criticism against crypto remains difficult to counter however: it is still incredibly circuitous to exchange crypto for goods and services on a daily basis - especially in a manner that stays true to Satoshi Nakamoto's original vision.

For instance, crypto credit cards allow you to easily buy almost anything using your crypto balance. However, this method still relies on either the Visa or Mastercard payment network to process the transaction. So while convenient, these credit cards do not circumvent financial institutions.

Other popular means of spending crypto also rely on intermediaries. Services such as BitPay or Purse allow you to purchase gift cards for Amazon, Uber, Google Play and so on. While these services are not traditional financial institutions, this method of spending crypto is ultimately a form of re-intermediation. BitPay or Purse take on the role of a payment processor instead of a credit card or a bank. It's not a solution to the crypto-as-money problem nor is it in line with Nakamoto's vision.

While some online retailers have started to accept direct crypto payments, uptake by customers has been tepid. For example, Overstock, a home furnishings and decoration retailer, accepts crypto payments since 2014. In the first three quarters of 2020, Overstock averaged just $30,000 to $50,000 in crypto payments weekly on revenue of nearly $2 billion. This is likely due to the nature of their customer base, as the Overstock's CEO explains: "Our demographic skews hard towards women and bitcoin purchasers tend to be men".

One use case which harnesses the unique characteristics of crypto payments is acceptance by privacy-enhancing services such as VPNs. By accepting crypto, VPNs allow their customers to remain anonymous while transacting electronically. This is undeniably appealing to those who value their privacy - as VPN customers typically do. Furthermore, a VPN provider does not need to know your name or address to deliver their service so there is no reason they should have this information in the first place.

The decoupling of payment and identity is impossible with traditional electronic payments based on fiat currency. Crypto circular economies take this idea a few steps further.

Crypto Circular Economies: The Radical Implications of a Simple Idea

(I use the terms 'bitcoin' and 'crypto' interchangeably in the text below.)

A crypto circular economy describes a "closed-loop system that designs out all of the corruption and headache of dealing with central bank-issued money". It is a "free market where you can trade any products or services for bitcoin, including daily needs like food, jobs and housing."

Spending crypto for your daily needs seems like a straightforward enough idea. It becomes radical when you consider that the means of exchange at the heart of the system is 'stateless': there is no government or institution backing it.

Bitcoin doesn't only separate money and state, it also separates markets and states. A Bitcoin circular economy is based only on supply and demand — no state regulations, bans, KYC, permits, subsidies or quotas are necessary. This creates meritocratic free markets, where your skills, ideas, character and effort matter more than the state's permission. (Emphasis added.)

KYC-Free Bitcoin Circular Economies: Free The Markets, Free The World

The absence of state control over both money and markets is the defining characteristic of a circular economy.

Crypto circular economies have popped up around the world. Some notable mentions include Bitcoin Beach in El Salvador, Bitcoin Lake in Guatemala and Bitcoin Ekasi in South Africa. For the moment, these all remain small-scale pilot initiatives. They are confined to a small area and count users in the hundreds or thousands at most. Still, they serve as valuable proofs-of-concept. Given the inherent scalability of cryptocurrency, there is no immediate technical impediment to expanding circular economies on a global scale.

It's no coincidence that circular economy projects are concentrated in the developing world. In the West, the dominant narrative surrounding crypto rarely mentions institutional failure. Yet democracy is on the decline globally, with only 20 percent of the world's population living in free countries as of 2021. This trend is also accelerating.

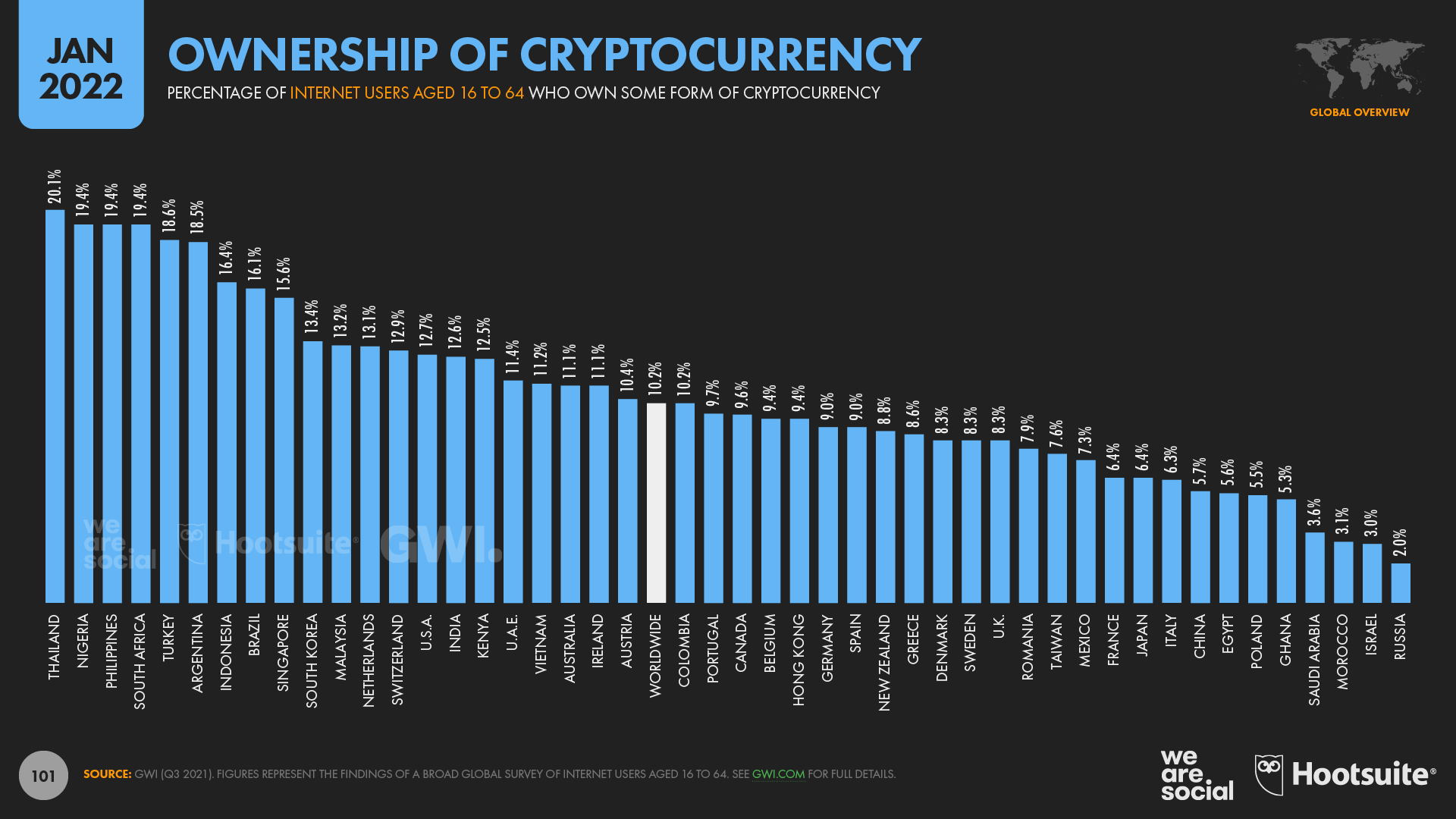

The global decline in freedom foments distrust and is accompanied by swelling potential for government failure. It is the citizens of less-free countries who will increasingly turn to crypto as means of regaining some measure of financial control over their lives. The five countries with the highest rates of crypto ownership are Thailand, Nigeria, Philippines, South Africa and Turkey. Of these countries, only South Africa is ranked as ‘free’.

Murmurs of discontent are also being heard in the developed world. The governments of some free countries have demonstrated a remarkable willingness to stifle dissent with financial strong-arming. People have started to take notice.

In early 2022, hundreds of Canadian truckers and thousands more of their supporters gathered in downtown Ottawa to protest COVID-19 containment measures. The so-called Freedom Convoy blockaded the capital for three weeks to get their point across. To finally quell the protests, the government invoked the Emergencies Act, which allowed law enforcement to freeze bank accounts and credit cards without a court order, among other sweeping powers. As a result, hundreds of financial accounts belonging to protesters were frozen. A number of Bitcoin addresses were also sanctioned to prevent crypto exchanges from transacting with them.

A judicial inquiry later determined that the Canadian government's use of emergency powers to stop the protests was necessary albeit "regrettable".

Even those who consider the government's response to the Freedom Convoy justified should be stunned at just how easily (and with how little oversight) their fellow citizens' finances can be subjected to the whims of the state. It doesn't take a big leap of the imagination to understand that this power is now just as readily available to the next government - one which might have less favorable political leanings to your own.

While admittedly an extreme example, the story of the Freedom Convoy helps to raise awareness of financial coercion by the state and the methods available to resist it. It helps one to better grasp the appeal of a means of exchange that is firmly outside of government purview.

Circular economies seem like a natural next step in the evolution of cryptocurrencies - especially if they are to ever shed their skin as a speculative asset.