VPNs and Digital Privacy: An Overview

VPNs can meaningfully bolster digital privacy for most users. Yet they still require you to place your trust in the practices and policies of the VPN provider.

Demand for virtual private networks is surging. The VPN market, worth $44.6 billion in 2022, is expected to grow to over $130 billion by 2030.

While VPNs are commonly seen as a tool to preserve digital privacy, this is not the purpose they were originally designed for.

A virtual private network connects an endpoint (e.g. a computer or smart phone) to a computer network over an insecure public medium such as the internet. For example, when you work from home, you most likely access your company’s network over a VPN. Likewise, your company smartphone also connects over a VPN when using a cellular connection to enable you to receive emails, view calendar appointments and exchange instant messages with your colleagues. In other words, a VPN mimics access to a network as if you were connected locally - say over WiFi or Ethernet cable.

Why use a commercial VPN?

The typical use case for commercial VPN services is different. Customers mainly use these to mask their ISP-assigned IP address. In this way, commercial VPNs function more like proxy servers - a middleman which take your requests and merely passes them on. Hiding your IP address offers some privacy benefits. It can also help you to circumvent geoblocking e.g. allowing you to access the Netflix libraries of other countries.

VPN connections are usually encrypted - a useful feature when using unsecured public internet connections, such as those available in airports or on public transport, because it can protect you from man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. An MITM attack is where someone with access to the router you are using to connect to the internet is, essentially, eavesdropping on your network traffic.

However, it’s worth noting that it’s now common practice for websites to default to an encrypted connection. (If you see ‘https://’ preceding the URL in your browser's address bar, your connection to that website is secure.) So while using a VPN brings the added benefit of encrypting all your network traffic (and not just the browser's traffic), this type of attack is less of a threat than it used to be in the time before HTTPS was ubiquitous.

A matter of trust

As already discussed, the data passing through your VPN connection is encrypted while it is in transit from your device to the VPN server. However, upon reaching the destination, it must be decrypted so that the server can pass on your requests to the websites and apps that you are trying to use.

This means that the VPN provider - the company that owns the server which you are connecting to - potentially has access to all of your network traffic. (This does not apply if you connect to a website over HTTPs, as illustrated above.) Seen from this angle, a VPN is no different to your internet service provider (ISP), which can also see all of your unencrypted network traffic.

Returning to the question of whether VPNs are good for privacy, we can see that a more fitting question might be: Do you trust your ISP or your VPN provider more?

In many parts of the world, ISPs form regional oligopolies. This a market condition where just a handful of firms dominate an industry. (Regional oligopolies are typical of many infrastructure-based markets such as public utilities or railroads.) As a result, ISPs rarely compete based on price or service quality. Customers don’t have the option of ‘voting with their wallets’. Lastly, the vast majority of customers are either oblivious or indifferent to privacy concerns, so these rarely factor in to their purchasing decisions.

The VPN market is fundamentally different. Consumers are free to change providers at the drop of a hat and there are hundreds to choose from. It’s also fair to argue that many VPN customers are at least somewhat privacy aware. A VPN's privacy claims are therefore likely to be subject to more scrutiny than an ISPs.

With this in mind, it seems that a VPN service has a greater incentive to protect user data than an ISP. In fact, their survival depends on it. Therefore, it’s reasonable to suggest that customers might be better off placing their trust in VPNs when it comes to privacy-related matters.

Unfortunately, reality resists such simple classification. The crux of the matter is that even savvy customers don’t have the means to verify a VPNs privacy claims and practices.

The ‘no logs’ policy touted by many VPN providers is a classic example. Customers have no way of ascertaining whether this claim is true. They have to take the providers word for it - until something happens that puts their statements to the test.

ExpressVPN servers seized in Turkey

In December 2016, Russia’s ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, was gunned down while speaking at an art exhibition in Ankara. The assassin, off-duty Turkish police officer, Mevlüt Mert Altintaş, was killed by security forces shortly afterwards.

During the subsequent 2017 investigation into the brazen assassination, Turkish authorities discovered that someone had logged into Mr Altintaş' Facebook and Gmail accounts, deleting conversations that may have been relevant to the investigation. The person had logged into these services using ExpressVPN to conceal their IP.

In an attempt to identify the person who deleted these conversations, Turkish authorities raided the data center which housed the ExpressVPN servers. The operation ultimately amounted to nothing. The servers contained no logs or other clues that could be used to trace the identity of the suspect. As of the time of writing, the identity of the person who deleted Mr Altintaş' Gmail and Facebook conversations remains unknown.

The Turkey case was a watershed moment for the VPN industry. A leading VPN provider’s ‘no-logs’ claims had been put to the test as a part of a major criminal investigation - the assassination of an important political figure, no less.

ExpressVPN had fully cooperated with authorities, just as any other company facing a similar situation would have. However, their operational security regimen was crafted in such a way as to prevent them from ever knowing the kind of information about their users that law enforcement was seeking. Their hands were tied by their own design.

What would have happened to ExpressVPN if authorities had found what they were looking for? It's more than likely that their business, which is based on trust, would have crumbled overnight. This is a good thing because it raises the stakes for VPN services. They are compelled to make good on their privacy promises or otherwise risk going under.

Readers should not take my depiction of this case as an endorsement of ExpressVPN. It would be shortsighted to base your confidence in a VPN provider on a single episode. Below you'll find an outline of some qualities to look for (and some to avoid) when choosing a VPN service that suits your needs.

What to look for in a VPN provider

Avoid free VPNs

The tried-and-true adage ‘if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product’ applies to VPNs just as it does to all other online services. Examples of free VPNs collecting and monetizing user data abound.

If you are determined not to pay, then the best option is to choose the free tier of a reputable premium VPN provider. You’ll likely have to deal with some bandwidth and connectivity limitations but it’s by far the safest option.

Avoid VPNs incorporated in the ‘Five Eyes’ countries

The Five Eyes describes the intelligence sharing coalition between the US, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK. These five countries are party to the UKUSA Agreement, a treaty establishing joint cooperation in the domain of signals intelligence. In 2013, the NSA leaks showed that intelligence agencies are siphoning private data directly off of tech company servers. Be wary of any digital services based in these countries.

No logs

Barring exceptional circumstances, such as a high-stakes criminal investigation as illustrated above, the ‘no logs’ claim is impossible to verify. Some services will go to great lengths to convince you otherwise, for example by hiring independent auditors to vet their infrastructure. But this just shifts the trust burden onto someone else: How do you know you can trust the auditor?

Furthermore, it’s impossible to run a VPN entirely without logs. For example, the service needs to know whether you paid and how long your subscription lasts for when you access their service. The VPN also need to make sure that you are staying within the limits regarding bandwidth, speed or the number of concurrent devices. This requires at least some tracking of the activity on their network i.e. there are logs. To claim otherwise is gimmicky at best.

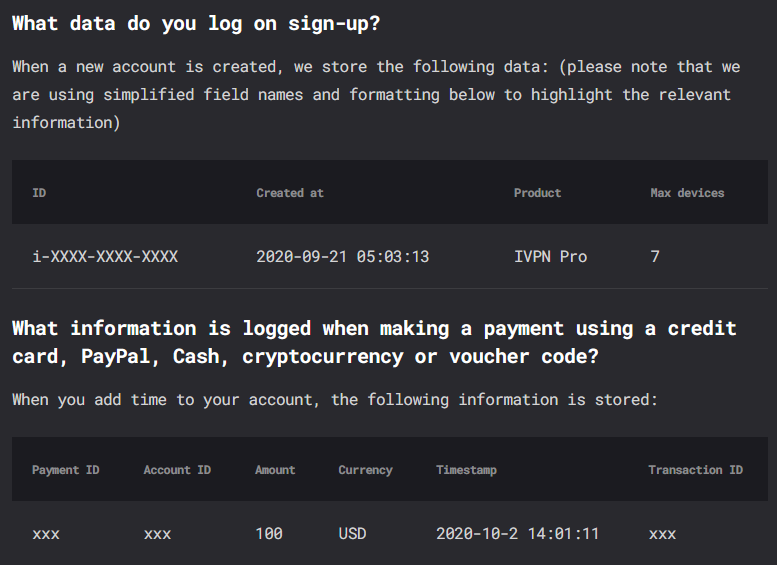

Instead, look for a VPN service that is transparent about the data that they collect and how they use it. A good example can be found in the privacy policy of IVPN. It describes in detail:

- What data is NOT collected.

- What data is collected - both upon signup and payment.

- How that data is used.

Although this still requires you to trust that the provider will remain true to their claims, it demonstrates a more nuanced approach to the topic of logging, which is usually indicative of a broader privacy mindset. More on that below.

Pseudonymous accounts; anonymous payment options

A VPN provider does not need your email address or any other personally identifiable information to provide their service. There is no reason you should divulge it to them. Some VPN services will now generate a numbered account ID for you upon sign up to avoid collecting any personal data. You use this ID to login instead of a user name and password.

The same applies to payments. Paying by credit card or PayPal requires you to submit personal data and your purchase becomes part of your financial records. To counter this, many VPNs now accept gift cards and cryptocurrency. Some even accept cash by mail.

Look for services with a refined and substantial privacy philosophy

The internet has arguably become the single most effective surveillance tool ever created. There is no single solution to protecting your online privacy. While a VPN has its uses, it does not guarantee you anonymity nor will it protect you from hackers, identity theft and other cyber threats - as VPN services will often claim on their websites.

Some VPN services are forthcoming about the limitations of their product. Mullvad VPN states this plainly in their ‘Change your online habits’ guide:

When protecting your online privacy, no single solution exists. Instead, it’s about changing your habits and using certain tools.

IVPN also provides educational material about privacy topics. (The article about privacy vs anonymity is worth a read.)

Both Mullvad and IVPN also go beyond educating users. They are active members of the privacy community. For example, Mullvad is currently campaigning against a proposed EU regulation that could eventually lead to government monitoring of private digital communication and possibly spell an end to encrypted chat apps.

VPNs: Useful but not a privacy guarantee

Commercial VPN services serve two purposes: they mask your IP address and encrypt your network data. (Although the latter only applies until that data reaches the VPN server.)

Masking your IP address adds a layer of protection but it is not enough to guarantee total privacy. It can also help to circumvent geoblocking and enable you to access sites that may be blocked by the government or your ISP.

Encrypting your network connection is also useful - particularly when using an untrusted internet connection while traveling or if you want to hide your data from prying eyes. (And assuming that you trust your VPN service with that very same data.)

For most users and in most cases, the protection offered by a VPN is a meaningful way to improve privacy - especially when combined with a change in online habits, such as preferring a privacy-friendly search engine and browser.

Those looking for more comprehensive privacy solutions should look further afield to software such as TOR or Tails.

Did you enjoy reading this article? Do you want to stay up-to-date with the latest stories about tech culture, information security and other modern phenomena?

If yes, please consider subscribing. It's free, and your support will enable me to write more and cover new topics in the future. Thank you!